Syd

(Sid?) Cohen

Syd

(Sid?) Cohen Syd

(Sid?) Cohen

Syd

(Sid?) Cohen

Johannesburg(?), South Africa

Combat Record

?

Story

Syd Cohen had just begun medical school when World War II began. He left school to enter the military and was accepted into the SAAF's flight school. Unusually large for the position, he was nevertheless in early 1942 assigned to fly fighters with 4 Sqn SAAF. His first "office" was the cockpit of a Curtiss Kittyhawk in North Africa.

Eventually, Cohen and 4 Sqn switched over to Spitfires. He and Jack Cohen had known each other in South Africa before World War II, and met again when Jack joined the squadron. Later in the war, Lionel Bloch would also join 4 Sqn. While 4 Sqn was still fighting in North Africa, Cohen's tour expired, but he signed up for a second and was posted to 11 Sqn SAAF, with which he reached Italy. Cohen had reached the rank of Captain by the time he left the service.

Leo Nomis must have known Cohen well, for he offers a fairly detailed description of the South African's experience:

Though not one of the spectacular fighter pilots which that era periodically produced, Syd had a unique combination of skill, endurance and the ability to lead with an almost uncanny calmness of spirit. Like all who have seen action, he was affected by it but it was a mark that was rarely visible in the nature of him and he returned to civilian life with an attitude that was probably more outwardly serene than most. He, as was the case with any who flew in the great conflict, never forgot the air but he settled into the routine of making a living on the ground and he went back to his medical studies in Johannesburg. (Nomis and Cull 1998)

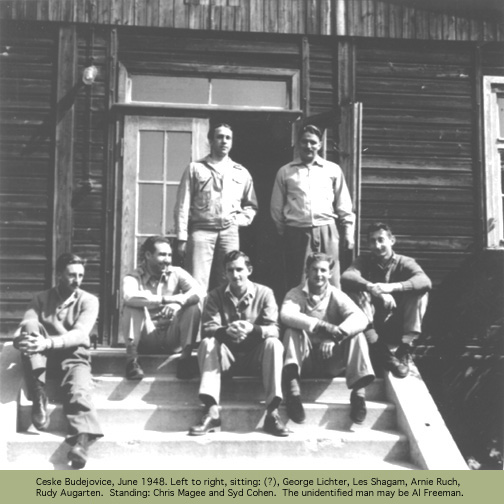

Syd was among a handful of pilots that Boris Senior lobbied to fly for Israel on his spring 1948 procurement trip to South Africa. Cohen and Shagam eventually signed up, and arrived in Israel in late June as passengers aboard one of the Dakotas Senior had acquired in South Africa. Within a few days, Cohen and Shagam found themselves in Ceske Budejovice, being introduced to fellow South African Arnie Ruch and American volunteers George Lichter, Rudy Augarten, Al Freeman, and Chris Magee. Boris Senior was there too.

After only a few days training, Cohen returned to Israel to join 101 Squadron at Herzliya, a field whose unpaved strip, Cohen believed, promoted accidents.

Cohen flew his first operational mission July 12 with Les Shagam to provide air cover over Mishmar HaYarden, where Maury Mann and Lionel Bloch had intercepted Syrian AT-6s the day before. Before he arrived there, the experienced Cohen decided to test-fire his guns and in doing so he may have saved his life and the life of anyone who would take up a S-199 in the future. When Cohen fired his cowl guns, he seriously holed his propeller. Shagam escorted him safely back to Herzliya, and recalls:

A problem with the Messerschmitt was that the guns fired through the propeller and there was trouble with the timing mechanism. (Syd Cohen) came back with three blades of his prop partially shot away. We developed a procedure then - from Herzliya we took off out to sea and as soon as we got up to about 1,000 feet, fired a burst from the guns to see what happened! (Cull et al 1994)

The exact reason for this remains unclear. The synchronization gear may have been ill suited to the Ju 211F's extra-wide propeller. Some of the pilots felt that perhaps the Czechoslovakian mechanics deliberately misfitted it. Maybe the gear itself malfunctioned with wear. Regardless, this was the first evidence of the phenomenon that the squadron could examine. The squadron pilots blamed the losses of Bob Vickman and Lionel Bloch in the two days previous squarely on this malfunction.

Leo

Nomis reached 101 Squadron on July 31 and met Syd Cohen, whom he described as

"imposing". They had actually met previously, at a party in the Western

Desert during the fall of 1942:

Leo

Nomis reached 101 Squadron on July 31 and met Syd Cohen, whom he described as

"imposing". They had actually met previously, at a party in the Western

Desert during the fall of 1942:

(Syd Cohen's) unmatched qualities as a pilot and a leader precipitated his immediate appointment as a flight commander in 101 Squadron after coming in from Budejovice in late June. To Syd, the fact that we were flying Messerschmitts seemed forever ironic and comical.

He looks different without a beard. At El Adem that autumn of 1942, Syd had a beard. I think of the night when we [members of 92 Squadron] were looking for the landing ground where the Spitfires were and the flat desolation of the Western Desert all seemed the same. We drove up to the mess tent of the South Africans. They were having a party. The South Africans always had brandy and it was the first time I met Syd. At two inches over six feet, he was at the tent flap with tin cups in his hands and he ordered us to have a drink. He called himself Cohen the Jew and he led everyone in singing ribald songs. We stayed there all night. Now we stand in the dust beside a stone hut in Israel and face each other again. The beard is gone but there is the same flat nose, the wide face, the calm eyes. (Nomis and Cull 1998)

Nomis was assigned to Cohen's B flight, and recalls one preflight briefing:

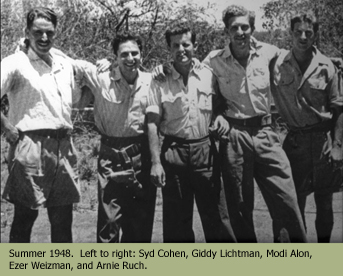

Syd Cohen arranges for me to go on a four-plane sector patrol. Giddy is appointed to lead the formation and the others are Ezer and Sandy.... When we go back outside, Syd unfolds a map on the ground. He points to the salient created by the Partition and, indicating that Tul Karm is the apex, he moves his finger along the approximate positions of the Arab lines. He looks at Giddy and says that we will stay away from them today. Tul Karm is eight miles due east of where we are standing (at Netanya airbase). (Nomis and Cull 1998)

As it turned out, Weizman developed an iol leak before take-off and did not participate.

Nomis, who shared a tent with Cohen and Arnie Ruch at Herzliya, tells a story he overheard Cohen telling Ruch:

There is a half-moon in the cloudless sky when I walk with Syd Cohen and Arnie Ruch on the road back to our quarters. They talk in Afrikaans sometimes and the jolly natured Arnie laughs at everything Syd says.... We near the lane and Syd is talking about when they got up to Italy in 1943 and he had met a girl in one of the villages outside Parma. She wouldn't have anything to do with him romantically because she said he looked like Jesus Christ. Syd says he shaved off the beard after that. Arnie laughs again and pulls at his tropical shorts. We turn through the garden and walk past the white buildings. In the tent Syd lights a kerosene lamp and our shadows appear large on the canvas. We get into the cots and roll the insect nets down and Syd extinguishes the lamp. We are all sleeping in our underwear. The voices from the buildings die away and the dogs behind the dining hall stop barking and then there is silence and darkness. A half hour later the jackals begin their wailing down the hill and the chorus is answered along the line and carried far off into the distance. The sound is like children crying in the night. (Nomis and Cull 1998)

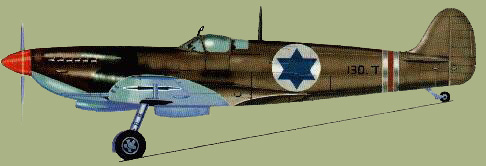

The first Spitfire, designated D-130, was configured as a photo-reconnaissance machine. Only experienced Spitfire pilots were allowed to fly it. At first the list was was limited to Modi Alon, Syd Cohen, Maury Mann, and Arnie Ruch (and, as soon as he arrived, Leo Nomis), but as more volunteers showed up, particularly Canadians, the number of pilots eligible to fly it expanded. The aircraft's first 101 Squadron flight, a shakedown, took place Aug. 5 with Syd Cohen at the controls.

During August 17's visit by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion to Netanya, Modi Alon scrambled Syd Cohen and four of his B flight pilots, if only for show in front of the prime minister. Leo Nomis recalled the event:

Everyone is milling about, when a shuftikite appears high overhead, a tiny speck against the wisps of cirrus clouds that are streaked across the deep blue above. The patrol aircraft had landed before the Rapides came in and everyone just looks upward and watches the intruder plane.

B Flight is on standby and (Syd) Cohen looks over at Modi to see what he is going to do. Ben-Gurion... is also looking at the sky, shading his eyes with his hand. Abruptly, Modi tells Cohen to scramble four planes. Cohen points to me and grabs Lichtman by the arm and shouts to Bill Pomerantz.

We start running to the nearby readiness jeep and we jump in; Cohen floors the throttle pedal when the motor starts. We head for the revetments. The rotund Pomerantz smiles skeptically, as we watch the shuftykite fast disappearing to the north. Everyone knows it is futile to scramble and, when we get to the standby Messerschmitts, Modi cancels it. A red flare arches up from behind the Ops tent and falls to earth out on the field, where it burns and sputters for a moment. The gesture for the Prime Minister has been made. An hour later Ben-Gurion leaves and the Rapides lift off slowly in the midday sun. (Cull et al 1994)

In

late August, Cohen discussed with Nomis his thoughts on the war:

In

late August, Cohen discussed with Nomis his thoughts on the war:

I walk with Syd Cohen to the tent at Kfar Shmaryahu. The afternoon is waning and we are off duty for the day. The side flaps of the tent are rolled up but the air inside is warm and we remove our shirts and lie down on the cots. Syd takes his high-top desert shoes off and we get under the nets to escape the harrassment of the flies and we talk about the war. This war. Syd discards his normally casual manner for a moment. He says that if he survives up here and if, in the end, the Jews are guaranteed their national homeland, he is going back to university in Johannesburg to complete his degree in medicine. He leans on his elbows beneath the transparent, curtain-like net and looks out to where the sun is bright on the white walls of the pension buildings. He says that the Jews need a decisive military victory, not just a moral one. Then, maybe, there will be hope for some kind of peace in the future. After a pause, he gets up from the cot and goes outside to the faucet for a drink of water. When he comes back he sits on the dge of his bed and says that the UN mediation isn't going to really solve it. He says that Bernadotte is weakening toward Arab demands and the only way the Jews are going to get what they want is to fight for it. I listen and what he says is something we all already know. He picks up a piece of paper and a pencil from the top of an ammunition box at the foot of the cot and, using the surface of the box to write on, he makes out the flight schedule for the next day. (Nomis and Cull 1998)

The day 101 Squadron returned to Herzliya, Cohen took D-130 out to snap some pictures of Gaza. Leo Nomis, returning from a patrol in a S-199, bumped into him:

When I come out of the (Ops) tent Syd Cohen is going by in a jeep with Croll (the squadron ops officer). They stop and I ride out to the Spitfire dispersal point with them. Syd is going on a PR flight to Gaza and as he puts on his gear I tell him about the shuftikite episode. He laughs and goes over and looks at the map which Croll seems eternally to have in his hand. A Messerschmitt is taking off and we can't hear anything for a minute. Syd wipes his mouth with his forearm. When he gets up on the wing of the Spitfire, Croll extends a revolver in a fabric holster toward him. He tells Croll he doesn't want it. He says they are too bulky to wear in the cockpit and that they are too dangerous to be carrying if you are captured. Croll agrees but says it is an order from headquarters that the reconnaissance pilots must wear a sidearm. Syd still doesn't want it. Croll looks at the ground beside the wing for a moment. He says it's not necessarily for use against the enemy. He says it's for Syd to use on himself if he is captured by irregulars. The statement amuses Syd. He takes the gun and straps it on and climbs into the cockpit. (Nomis and Cull 1998)

In mid-September, Arab flak had begun to fire at the Israelis in earnest. On one trip to Gaza, flak bursts chased Cohen out over the Mediterranean.

On the morning of Sept. 24, six Velvetta 1 Spitfires left Kunovice, Czechoslovakia for Niksic, Yugoslavia, 300 miles away, with Modi Alon, Boris Senior, Syd Cohen, and Tuxie Blau joining Sam Pomerance and Jack Cohen behind the controls. Boris Senior had opted to give the last pilot slot to Tuxie Blau over Arnold Ruch although Ruch had more experience. Ruch traveled in the C-54 (DC-4) that led the group. Of the seven available fighter pilots, all but Alon and Pomerance hailed from South Africa. Without the built-in radios, the pilots communicated as well as they could - which was poorly - with walkie-talkies. Blau forgot to lower his landing gear at Niksic and damaged his plane but was unhurt.

(names painted on Spits in Velvetta 1?)

The five airworthy Spitfires, led by the C-54 which also contained rescue equipment, took off for Israel three days later. The route took them over Albania and around Greece, whose airspace was avoided due to that country's civil war. At the Greek island of Rhodes, by the Turkish coast, the planes would make a right turn for Israel.

Two

hours into the flight, Boris Senior and Modi Alon felt that their reserve fuel

tanks were empty and that they did not have enough fuel on board to make Israel.

They landed at Rhodes while the others continued on 750 miles to Israel. Over

Israel, the Mother Ship bade goodbye and headed for Ekron, while the three remaining

Spitfires aimed for Ramat David. The trip, the longest ever by a Spitfire, lasted

just over six hours. Pomerance landed first, followed by Syd Cohen then Jack

Cohen.

Two

hours into the flight, Boris Senior and Modi Alon felt that their reserve fuel

tanks were empty and that they did not have enough fuel on board to make Israel.

They landed at Rhodes while the others continued on 750 miles to Israel. Over

Israel, the Mother Ship bade goodbye and headed for Ekron, while the three remaining

Spitfires aimed for Ramat David. The trip, the longest ever by a Spitfire, lasted

just over six hours. Pomerance landed first, followed by Syd Cohen then Jack

Cohen.

At the airfield, amid great excitement, a welcoming ceremony had been prepared. The leading personalities of the new nation and its armed forces were waiting there. When we managed to get out of the cockpits after sitting tightly strapped in all that time, even though we could hardly stand up straight, we had to get in the middle of the celebrations, which also included the usual dancing. (J. Cohen 2000)

The three successful Velvetta pilots held a post mortem to work out what had gone wrong with the planes that had to land in Rhodes. The three investigators discovered that each of them had experienced the same fuel gauge problem on the flight, and each had successfully dealt with it the same way. They decided that the trouble lay in the wing tanks. By process of elimination, they determined that the problem lay in the wing tanks' breather pipes that had been fitted in Kunovice. The angled, open end faced forward and the pressure of the wind through the pipe pressurized the tanks, forcing fuel through fuel lines and pump to the long-range tank, keeping it full and keeping the gauges registering a full tank.

Each Spitfire drew fuel from the long-range slipper tank before engaging the main tank. The pilots should have seen the slipper tank's fuel gauge drop as fuel was used up, but because the slipper tank was continuously topped off by wind pressure, they did not.

Senior and Alon had both assumed the gauges were faulty, whereas the other three assumed correctly that the problem lay in surplus fuel feeding. Senior and Alon, suspecting their slipper tanks were low on fuel, both switched on their wing-tank fuel booster pumps, which started pumping fuel into the full long-range tank. As a result, the slipper tank relief valves just dumped the fuel as it was pumped in; Senior and Alon were just pumping fuel overboard.

Another frightening finding in the debrief of Velvetta 1 was the condition of the parachutes the pilots wore. They discovered that the chutes had not been checked in Czechoslovakia and that the harnesses on some of them had been eaten through by rats. A more thorough inspection of parachutes was put on the "to do" list.

The mid-October offensive called Operation Yoav tasked four of 101 Squadron's five Spitfires with escort of Beaufighters to Al Arish. One of the Spitfires went unserviceable, but the other three left Herzliya in the Oct. 15 first strike to hook up with two Beaufighters from Ramat David. The aircraft hit the Al Arish airbase at 17:40, with the Beaufighters bombing and both Beaufighters and Spitfires, piloted by Cohen, Rudy Augarten, and a third man, strafing. They destroyed four REAF Spitfires on the ground, demolished a hangar, and cratered the runway so badly it prevented any take-offs, before AA forced the Israelis to retreat.

Cohen had an unfortunate front-row seat for one of 101 Squadron's biggest tragedies. On the afternoon of Oct. 16, Syd Cohen and Maury Mann sat in the new Spitfires at Herzliya, awaiting clearance to take off. Modi Alon and Ezer Weizman were returning from a S-199 ground attack mission against the retreating Egyptians near Ashdod. Sitting there waiting, Cohen and Mann had possibly the best view of Modi's nose-dive into the ground subsequent death. Syd Cohen recalled Alon's charisma:

I remember one morning, after a particularly bad night in Tel Aviv when we literally ripped the town apart, he called us together and gave us a good talking to. He said that he associated such behavior with the British army during the mandate rule. He said that he felt let down by our behavior, and he asked us to refrain from such acts in the future. The incredible thing was, we all sat there like little lambs. If anyone with lesser personality had tried to give us hotshots such a talk, I don't know what we would have done, but we took it from him as if he were our equal. He was quite an inspiring guy. (Yonay 1993)

After Alon, the squadron's commanding officer, died on Oct. 16, the question of who would succeed him arose. The choice eventually boiled down to one of the squadron's flight commanders, ironically the two who had the best view of Alon's crash: Syd Cohen and Maury Mann. Mann, the 101's XO, desired to take command but Air HQ felt he was too aggressive (Red Finkel, pers.comm.) - and, in fact, he had crashed a S-199 earlier that day. Either through injury or temperament, Mann was disqualified from consideration, and in fact lost his flight leader status. Air HQ chose the experienced and greatly respected Syd Cohen to take over Alon's mantle, and he would lead the squadron throughout the rest of the war. Augarten and Weizman were promoted to flight leader.

Syd Cohen took over as 101's commanding officer and Syd Antin, like many, were impressed with his leadership:

Syd Cohen was a great guy. Everybody loved him. He commanded a great deal of respect. He had a great deal of wisdom for his age and experience and people respected that.

On Nov. 9, 101 Squadron moved south to Chatzor to take a position closer to the southern front, where it flew most missions. One advantage of the more southerly location was that it was further along the route that the daily shuftikite flew and so gave more time for an intercept. The "shuftikite", a weekly reconnaissance aircraft, had since since May 24 always flown the same route: it entered Israeli territory from the eastern Galilee, overflew Ramat David, then continued south through the Negev. Its noon-time flights also earned it the nickname "Noon Charlie". Flying in mid-day at 30,000, it left clear vapor trails in the sky. Israeli officials were convinced it was an Iraqi Mosquito.

Late in the morning of Nov. 20, 101 Squadron at its new base at Chatzor received a phone call from Ramat David that the shuftikite had been spotted. While CO Syd Cohen headed for the control tower with binoculars, Wayne Peake scrambled in a Mustang. Cohen tracked the shuftikite while guiding Peake on the radio to a position behind it. The unidentified airplane probably sighted Peake's Mustang because for the first time, it headed west over the Mediterranean rather than continuing south.

Reaching the intruder's altitude, Peake was suffering blurred vision and almost passed out - his oxygen system was malfunctioning to some degree.

As the shuftykite's contrails came into view, Cohen guided Peake right to it, but Peake missed the intercept as he was too high. Cohen told him to dive, and Peake rolled over and found the target, which with his blurred vision he thought was a four-engine bomber. He let loose a stream of .50 caliber and hosed the shuftykite until his guns jammed. Syd Cohen recalled:

"It was going away and Peake cursing like hell on the radio and almost crying because he couldn't fire another shot, but suddenly I noticed that the vapor trails were getting thicker and thicker, and then I saw fire, and the next thing I knew that thing just disintegrated in the air." (Yonay 1993)

Upon observing the explosion, Ezer Weizman took the squadron's Seabee runabout to investigate the crash site off the coast of moshav Dor, south of Haifa, but he only found wreckage floating on the surface.

On landing, Peake was convinced he had shot down a four-engined Halifax bomber, but it was later proven that it actually was a two-engined Mosquito PR.34 (numbered VL625) from 13 Sqn RAF, based at RAF Kabrit near the Suez Canal. Peake's condition had probably given him double-vision, thus making the victim seem to have twice as many engines.

This was the last RAF flight over Israel proper.

(Take part in Velvetta 2?)

In November, Gordon Levett transferred into 101 Squadron. He first met the pilots, and Syd Cohen, in a bar - the Galei Yam in Tel Aviv, of course.

That evening I packed my possessions into a rucksack and went to the Galei Yam Bar facing the beach in Tel Aviv, the fighter pilots' favourite watering hole. I knew most of the pilots. There were several of them, including Syd Cohen the commanding officer, sitting at tables drinking thin, local beer. They all wore vivid red baseball hats. There was no bar to lean on. It seems only the British like to drink standing up.... At midnight we stole a large American station wagon and drove the 20 odd miles to Qastina.... For several months the operation of Israel's sole fighter squadron depended upon stolen cars. We learned how to rip out ignition wires and by-pass the ignition key. The police collected our booty regularly from the aerodrome. It became known as Syd's used car lot. (Levett 1994)

Levett's first operational sortie took place on Dec. 28, under Syd Cohen's wing. During a breakfast of cold hard-boiled eggs and green salad with olives and cottage cheese washed down with black coffee, the two pilots prepared for an early day.

It was still dark. Syd and I were the only people in the mess apart from the cook. We were wearing casual mufti, without wings or badges of rank. We did not look like fighter pilots breakfasting before dawn patrol. I could hear our two Merlins being tested distantly in the darkness. Dawn Patrol! I felt a bit like David Niven or Errol Flynn. I promised myself I would buy a white silk scarf. Syd was the calm, reassuring Spencer Tracy type. I felt confident he would not lead me into undue trouble. Nevertheless my ashtray was full by the time we left the table to go to our Spitfires. (Levett 1994)

Cohen and Levett took out a pair of Spitfires with two 250-pound bombs each to patrol the Khan Yunis-Rafah-Gaza front. They found a train heading southwest away from Rafah and dove on it.

Moderate anti-aircraft fire weaved pink, black and white filigree patterns around us as we circled the train and prepared to attack. Syd went in first and dive-bombed twice. His first bomb missed completely, his second was a near miss. It was my turn. Both my bombs missed by a mile. We had shifted a lot of sand. We then strafed the locomotive several times. I was astonished at the clatter and the recoil effect on the Spitfire as the guns fired. I was so absorbed by the puffs of sand as my bullets hit the desert that I nearly flew into the train. It spurted steam and stopped. Passengers were jumping out and scrambling underneath. Mothers were handing down children and babies from the windows. After our sixth or seventh pass we circled, looking down at our handiwork. The locomotive was badly damaged. By unspoken agreement neither Syd or I had attacked the passenger coaches. Our meek flight hit the headlines. According to the press we had destroyed a vital ammunition train and caused heavy losses among Egyptian troops on the train. Truth is indeed the first casualty of war. (Levett 1994)

The final day of 1948 saw 101 Squadron attack Bir Hama, an Egyptian airfield it had only discovered a week earlier. Denny Wilson, Syd Cohen, and a third pilot attacked in Spitfires, two with bombs and one as top cover. Wilson's flight log indicates that he dive-bombed before patrolling the airspace near the Egyptian base. He recalled:

On December 31, 1948, while flying a Spitfire (White 15) on a patrol over the Sinai, I spotted an Egyptian aircraft - an Italian Fiat (Macchi) - coming back to its airfield at Bir Hama. He was below me and I shot him down - the pilot bailed out. (Bracken 1995)

Two REAF Macchis were destroyed on the ground, one while taxiing. On the way back, Wilson and Cohen detoured toward Faluja.

Near the Faluja pocket, I caught an Egyptian Spit flying escort for a C-46, which was dropping canisters and supplies. I just slid in behind this Spit. He started to make a tight turn but I tightened with him. We were so short of ammunition, we'd been asked not to use our cannons. So I machine-gunned his engine cowlings. He spiraled down and blew up. (Cull et al 1994)

After this fight, Wilson and Cohen joined up with a pair of Israeli Spitfires that were strafing a truck convoy on the Al Auja-Abu Ageila road.

We strafed them repeatedly. We had no idea of the number of transport we destroyed. (Cull et al 1994)

After the war ended, Syd Cohen returned to South Africa to work on a medical degree and afterward emigrated to Israel. He became a physician in the IDF. Cohen retired as El Al's chief medical officer in 2000 (?) but continues to serve as a consultant to his successor.