Avia S-199

Although built in Czechoslovakia from surplus German airframes and engines, the Avia S-199 had only one real moment in the sun, flying (and crashing) under Israeli (well, and Egyptian and Syrian) skies during the War of Independence.

The pedigree of the Avia goes back beyond the Spanish Civil War, and begins with the initial design of the Bf 109, but for our purposes, we'll pick things up in post-war Czechoslovakia....

Czechoslovakian factories had manufactured arms for the Germans during World War II. Avia, a Skoda Works subsidiary, produced aircraft, including the Arado Ar 96, for the Luftwaffe. Germany intended to produce the Bf 109G-14 at Avia starting in early 1945, but the course of war overtook those plans. When Germany pulled out of Czechoslovakia, it left much of the manufacturing capacity intact, and after the war, the Czechoslovakian military initiated production of the type for the country’s new air force.

Avia test pilot Petr Siroky flew the first example, designated a C-10 with radio number V-9, on its maiden flight 22 February 1946. It was powered by a Daimler-Benz DB 605AM engine, one of a small stock left in the country. The wing bulges for wide wheels, breech blisters, non-retractable tail wheel, and trailing fin extensions on the rudder leave no doubt that the C-10 was based on the G-14 variant of the Bf 109.

Avia, and licensee Aero, eventually fitted 29 airframes with DB 605AM engines in a single-seat fighter called the S-99 and two as a dual-seat CS-99 trainer, essentially a Bf 109G-12.

Unfortunately for Avia, fire swept through the building that housed the Daimler-Benz engines, destroying them all. But Czechoslovakian factories could still provide large numbers of the Junkers Jumo 211F engines they had produced during the war to power Heinkel He 111H bombers, and Avia’s engineers decided to try to install it in the S-99.

Both the Jumo 211 and the DB 605 were 12-cylinder, inverted-V, liquid-cooled engines, but the Jumo 211F produced only 75% of the DB 605AM’s power at takeoff and less than 85% of its maximum continuous power. The two engines weighed about the same, but the Jumo drove the massive VS 11 propeller that produced much more torque and P-factor (airflow twisting force) than the standard fighter propeller married to the DB 605. The VS 11 was wood coated with a thin layer of plastic with leading edges of brass.

Nor did the Jumo 211 allow a cannon to fire through the spinner hub. Forced to remove the standard 20mm MG 151/20 from that position, Avia installed what the Luftwaffe called the Rüstsatz 6: a MG 151/20 gun pod with 120 rounds per gun under each wing. The cowl guns remained 13mm MG 131 machine guns with 300 rounds per gun. The ETC 50/VIId bomb rack could in theory carry up to four 70kg bombs or a 300L drop tank. In practice, the S-199 was limited to two 70kg bombs because the load impinged on its already dubious performance and handling.

The new aircraft’s maiden flight took place 24 April 1947. It was underpowered and difficult to control on the ground and in the air - but at least it flew and it packed a punch.

Like in most Bf 109s, the cabin was not pressurized. The ailerons and the rudders were fabric covered. Pilots cranked a wheel to operate the flaps, but the slats on the wings’ leading edges deployed and retracted automatically. Rudder trim was set before takeoff and could not be adjusted from the cockpit.

Avia would build a few versions, totaling 450 single-seat S-199s and 82 CS-199 dual-seat trainers (serial numbers 501-582) through 1949. The aircraft proved workable and stayed in Czechoslovakian service until 1957.

Otto Felix, a Haganah agent searching for arms in Czechoslovakia, reported that Avia had 25 of these aircraft cobbled together from surplus parts for sale in December 1947. The Haganah, optimistic that it could procure American fighters, declined the offer at first, but as the international arms embargo cracked down, it reconsidered.

Outside the United States, the Haganah had considered alternatives to the S-199s but for one reason or another, the deals fell apart. Boris Senior, sent to his native South Africa to try to procure arms, found 50 P-40 fighters, previously sold for $1,200 and about to be scrapped. South Africa, however, refused export permits for such obviously military goods and the logistics of smuggling them out of the country proved too much of an obstacle.

On April 23, Otto Felix purchased ten Avia S-199s for the obnoxiously high sum of $1.8 million ($13 million in 2001 dollars). Each empty airplane cost $44,600, its associated equipment another $6,890, and ammunition and ordnance $120,229 - for ten planes, that totals $1,717,190. The remainder of the $1.8 million bought the services of Czechoslovakian ferry pilots. That sum must be looked at in the context of a time when a surplus P-51D could be bought for $4,000. Still, Felix took an option on 15 more.

Shortly after Felix's agreement to purchase the S-199s, Al Schwimmer - possibly the most productive of all the Haganah's purchasing agents - found 25 war-surplus P-47 Thunderbolts for sale in Mexico for $1 million. The Haganah turned Schwimmer down and held to the agreement with the Czechoslovakians. Whether they did this for the sake of honor or because the European deal included training is unknown.

The subsequent arrests in Rhodes, Greece of Israeli pilots ferrying Ansons forestalled the ferry portion of the original plan, which called for stops in Italy and Greece on the way to the future Israel. Transport by land or sea was ruled out as too slow, so a slew of newly acquired Curtiss C-46 Commandos would form an airbridgefrom Zatec (codenamed "Etzion" but called "Zebra" by the American volunteers) to Ajaccio, Corsica to Ekron in a series of flights called Balak missions.

On May 6, two Machal volunteers (Lou Lenart and Milton Rubenfeld) and eight Israeli Sherut Avir pilots (Modi Alon, Ezer Weizman, Jacob Ben-Chaim, Pinchas Ben-Porat, Itzchak Hennenson, Misha Kenner, Nachman Me'iri, and the immigrant Eddie Cohen) left Sde Dov on a leased Pan African Air Charter DC-3. It hopped to Cyprus, Rome, then Geneva. From Geneva, the group took a train to Zurich and from there took a Czechoslovakian Airline DC-3 to Prague. After two days at a dingy Prague hotel, they flew to Ceske Budejovice aboard a military Ju 52. Assigned a barracks and Luftwaffe flight jackets, they began training.

Before they could take control of the plane their Czechoslovakian hosts had nicknamed "the mule" (mezek, in Czech), the pilots received brief instruction in dual-control Avia C-21B trainers (a Czechoslovakian version of the Arado Ar 96B). The instructors at the Ceske Budejovice airfield were Czechoslovakian veterans of the RAF. A few flights in the C-21B re-awakened old skills in the pilots who had flown fighter aircraft before. They also quickly and firmly rejected any hope that the Israelis who had only flown light civil aircraft in the past could be quickly converted into fighter pilots. Only those pilots with previous fighter experience - Alon, Weizman, Rubenfeld, Lenart, and Cohen - were allowed to move on to the next step in the course, which introduced the CS-199, a dual-seat trainer version of the S-199.

Besides weight and low power, the S-199's Jumo engine had another drawback. The huge prop created much torque, and pilots needed full right rudder to compensate. With no way to adjust rudder trim, pilots had to constantly fight the airplane while it was on the ground. Lou Lenart became the first of Israel's pilots to solo in a S-199 on May 15, and learned of the plane's tendency to slew the hard way:

As Lenart sat strapped down in his cockpit, the only thing he could see in front was the Messerschmitt's huge nose pointed skyward. Until his plane was traveling fast enough so that its tail came up, he had to watch the runway markings on his side, or fix on a distant tree or building for direction.

But the Czech field was only an expanse of gray-green grass blended seamlessly into the gray, dreary countryside. There were no runway markings, no trees in the distance to navigate by. When his instructor jumped off the wing and barked something in Czech that Lenart assumed was an order to take off, he pushed the throttle forward and let go of the brakes. When his speed gauge indicated he was going fast enough, he flicked his stick forward to raise the tail, and got ready to take off.

To his horror, as the Messerschmitt's huge nose came down, he suddenly found himself speeding between two huge hangars, heading straight for a tall chain-link fence. He had no idea where he was, or how the buildings suddenly got in front of him. Cursing and pulling hard on the stick, he managed to lift the plane over the fence, but he was not yet going fast enough and the Messerschmitt promptly dropped back down on the other side. Fighting to keep it from cartwheeling or smashing belly-first into the ground, Lenart managed to keep it skimming the grass until it picked up enough speed, and then pulled it up in the air. (Yonay 1993)

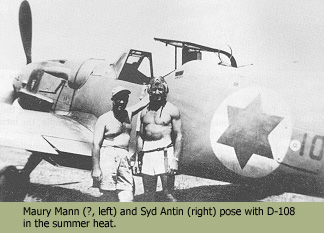

Syd Antin seemed to handle the S-199 well enough, but he is throroughly versed in its deficiencies:

It had very narrow landing gear, for which reason it ground-looped very easily and several of our pilots ground-looped it. I never did. I was fortunate, I'm not saying that in a bragging way, but I managed to handle it OK. I could understand and sympathize with anybody who had problems with it because it was very delicate.

Another terrible thing about it was you could not open the canopy in flight. It was fixed such that you either had it closed and locked or you could jettison it completely if you got into an emergency situation where you had to bail, of course. There was nothing in between. That was not good. Another thing even worse... is that fact that it had two .30-caliber machine guns in the cowl synchronized to fire through a three-bladed, paddle-bladed, wooden prop. We had at least two or three of our pilots experienced the synch going out and shooting off their own props. That was a hell of a situation....

I remember, too, the hydraulic system wasn't buffered. You had to push a button to put the landing gear down. It operated on a hydraulic system. If you didn't get your thumb off that button real fast after you pushed it, the pressure of the hydraulic fluid building up in the system would pop that goddamned button back out at you - it would almost break your thumb. (Antin, pers. comm.)

Leo Nomis summarized the plane:

...With the lesser horsepower (of the Jumo versus the Daimler-Benz engine), the machine was found to have high take-off and landing speeds, while the narrow gauge of the undercarriage, along with a monstrous torque, frequently caused dangerous direction deviations on the ground. The aircraft was considered worthy once airborne but its potential for unmanageable behavior was indicated by the name Mezec which was standardly applied to it.

The Messerschmitt (as the 101 called the S-199) is a short-range fighter. It holds less than 90 Imperial gallons of fuel and it has a flight endurance of something under two hours at a cruising speed of 310 km/h. The Czech versions are armed with two 20-mm cannon which are oddly slung beneath each wing and two 7-mm machine guns are mounted along the engine, under the cowling panels, and are synchronized to fire through the propeller. Racks to accommodate 250-kg bombs could be employed also and for all its faults it was a formidable war machine. (Nomis and Cull 1998)

Gordon Levett wrote:

The (Avia) was not popular with the pilots. It was, suprisingly, much smaller than the Spitfire or Mustang. With its splayed feet, upside-down engine, paddle-bladed propeller and ugly, bulbous spinner, it looked waspish and business-like.... Like the Spitfire, its undercarriage retracted outwards and the landing wheels were narrowly close together. It was a tricky aeroplane to handle on the ground, particularly with a cross-wind, and had a tendency with inexperienced pilots to ground-loop on landing and sometimes finish up on its back. Worse, the cockpit hood was hinged on the starboard side and was pulled over the pilot's head to lock on the port side, instead of sliding backwards and forwards like most other fighters. This meant that pilots had to take-off or land with the hood shut, trapping the pilot inside if the aircraft should finish up on its back. The entire squadron spent most of one afternoon releasing an unhurt pilot who was trapped in his upside down Messerschmitt after somersaulting on landing, with the ground soaked in petrol and the petrol tanks dripping relentlessly. I can still hear today his screams begging us to be careful and not cause a spark. (Levett 1994)

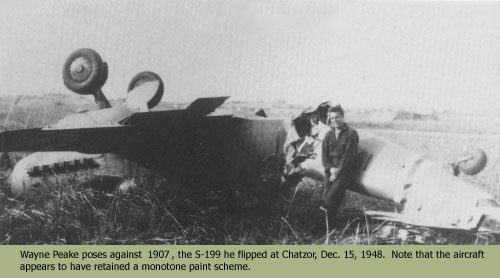

The trapped pilot was probably Wayne Peake, who was the last to lose a S-199 when he flipped his plane Dec. 15.

The S-199s were such a handful, the 101 pilots took unusually extreme caution in landing them.

Normally when you land a fighter, you come over the field, make a 360-degree turn and lower flaps and gear. That's when you're at your most vulnerable, so you don't want to stay that way. You land as fast and as quickly as possible. Now in the S-199s, we landed them like Fortresses (B-17s). We took long sweeping passes over the field until our speed dropped, then landed. (Finkel, pers. comm.)

The aircraft were plagued with other problems, too. On one scramble, Finkel pulled the starter on one and the handle came off in his hand. Landing gear routinely would not descend without some pilot-induced bumping and shaking. Pilots raised and lowered the manually operated flaps with a handwheel on the left side of the cockpit and had to either wear a glove on the left hand or risk blisters.

The aforementioned flaws led the squadron to adopt a dark hobby. Anytime an S-199 would come in to land, pilots would come out to watch and bet on the outcome. Red Finkel remembers one occasion, probably on Sept. 9:

"Some pilot was coming in - I don't remember who it was, I think it was Sandy Jacobs - and Bill Pomerantz and I were standing there watching him. Bill and I made a bet and sure enough, Sandy cracked it up. I asked Bill for the money, and he looked at me with this expression on his face and said, 'You wouldn't take money from a tragedy, would you?'" (Finkel, pers. comm.)

The S-199s would flip over so frequently that the Yemenite farmers working near the airfield got into a routine: every time a S-199 overturned, the farmers would right it with the bamboo poles they normally used to prop up fruit-laden banana trees.

On the other hand, Gordon Levett had some kind words for the type:

In mock dog-fights, we concluded that the Messerschmitt could out-climb, out-dive and out-zoom the Spitfire and Mustang. The Spitfire could out-turn the Messerschmitt, the most important manoeuvre in air combat, and both could out-turn the Mustang. The Mustang was the fastest, the Messerschmitt the slowest, though there was not much in it. The Mustang had the best visibility, important for a fighter aircraft, the Messerschmitt the worst. The Spitfire cockpit fitted like a glove, the Messerschmitt like a strait-jacket, the Mustang like a too comfortable armchair. The Spitfire had two 20-mm cannon and four .303 machine guns (sic, actually, the Spits had two .50s, not four .303s), the Mustang six 12.7-mm machine guns (a.k.a. .50 caliber), and the Messerschmitt two 20-mm cannon and two 7.92-mm machine guns synchronised to fire through the arc of the propeller.... Despite the pros and cons the Spitfire was everyone's first choice. (Levett 1994)

On the other hand, Chris Magee noted that the Avia "sure didn't climb like any homesick angel." (Weiss and Weiss, 1998)

By May 14, the day of the declaration of statehood, the ten S-199s Israel had purchased in April were ready to be dismantled for shipping. They awaited only pilots.

On May 18, the pilots in training at Ceske Budejovice learned that two Egyptian C-47s that day had bombed Tel Aviv's central bus terminal, killing 42 people and demanded to return to Israel. Their Czechoslovakian instructors unsuccessfully tried to convince the pilots to stay for at least a few days more training - the Israeli pilots had not yet undergone air-to-air or air-to-ground gunnery lessons. The Israelis insisted, saying they'd practice gunnery on real targets, and the five former combat pilots who passed the training course the next day moved from Ceske Budejovice to Zatec airfield, the headquarters of Israel's airlift operations.

The morning of May 20, the pilots and a handful of Czechoslovakian mechanics squeezed into a C-54 Skymaster beside a disassembled S-199, ammunition, and bombs. Each S-199 had the wings and propeller (and maybe the horizontal stabilizer) shipped independently from the rest of the fuselage. More than 11 hours later, they landed at Ekron. The next night (May 21), another S-199 arrived in a C-46 (serial number RX-138). On May 22, a third flew into the country inside the C-54.

Israel suffered its first S-199 loss on May 23, even before any flew under their own power. Two C-46s (RX-130 carrying bombs on the Balak 10 mission and RX-136 with a fourth S-199 as Balak 11) flew from Zatec to Israel. A thick fog enveloped Ekron and people on the ground lit fires to guide in the cargo planes. RX-130 landed uneventfully, but RX-136, piloted by Norman Moonitz, headed instead for Sde Dov. The gunners at that field did not expect an inbound flight and opened fire at the C-46 through the fog. Having abandoned the landing and flying through the countryside, RX-136 crashed on a gentle slope south of Latrun. The S-199 fuselage broke free on impact and slid forward into the cockpit, killing the Polish-born American navigator, Moshe Rosenbaum, and putting Moonitz in the hospital for two weeks.

The imported Czechoslovakian mechanics worked to assemble the fighter planes. In order to keep the presence of the airplanes secret, the crews at Ekron hid the them under camouflage nets. IDF General Staff was pushing for use of the aircraft, but the fledgling Cheyl Ha'Avir resisted. Cheyl Ha'Avir commander Aharon Remez reported to Prime Minister Ben-Gurion on May 28:

...The Knives were not ready at 01:00. The bombs were not ready and we do not have an armorer. There was something missing in the bombs. The Czech technicians could not load the guns. (Huertas 1998)

The aircraft were still in preparation the next morning. Remez wrote Ben-Gurion that morning, May 29:

"The Messerschmitts did not attack. The bombs the fuel and the brakes were not ready. They will be ready at 11:00." (Huertas 1998)

By the end of the day, four S-199s (later recorded as D-101 to D-104) were ready to fly. The aircraft hadn't even taken off for test flights. Their first flights in Israel would also be their first missions. The original plan for first use of the new fighters had been to make a surprise attack on Al Arish, but this was abandoned in light of a pressing Egyptian column south of Tel Aviv - in fact, a mere 20 km south of Ekron itself. The Egyptians, which included the Egyptian army's Second Brigade, had been stalled by a blown bridge 32 km south of Tel Aviv and the lightly armed remnants of the Givati Brigade. The Egyptians were estimated to have 500 vehicles, among them ten tanks.

The Givati commander asked for air support, but Remez wasn't keen to send his S-199s to help - he still wanted to attack the Al Arish airbase. Finally, the IDF committed to helping the Givati Brigade and the brigade commander rushed to Ekron to brief the pilots. The IDF rejected a similar request for air support from the Seventh Brigade, which was facing Jordanians at Latrun.

The four Avias, loaded with two 70-kg bombs apiece, took off to attack the Egyptians. The S-199s had no radios and no oxygen.

The official report of the operation reads as follows:

At 1945 local, a four-aircraft formation took off to attack a large column of Egyptian vehicles, between Ashdod and Gas'ser Ishdod, which had just stopped on the southern side of a destroyed bridge:

(1) - The leader, Lou Lenart, approached Ishdod from the north and dropped his bombs in the center of the village. He observed the largest vehicle concentration at the road curve about 300 meters south of Ashdod. His second pass was from southeast to northwest. His third pass was from north to south and in both he strafed with his machine guns since the cannon ceased firing after the first ten rounds. The AA fire was very intense and most of it came from 40mm guns. He landed at 2025.

(2) - Modi Alon approached from the northeast. South of the bridge, he observed a lot of vehicles and also many more vehicles were observed east of Ishdod. He dropped his bombs on the vehicles on the road. On his second pass, he attacked from east to west and on his third from north to south. In his passes, he exhausted his ammunition and returned home flying over the sea. The AA fire was heavy. He estimates the number of vehicles in hundreds. Upon landing at Ekron, his left brake did not function and he could not maintain a straight line as a result. Finally, he performed a ground loop, the left tire exploded, and the wing tip struck the ground and was damaged. He landed at 2005.

(3) - Ezer Weizman attacked from south to north. At first, he witnessed about 20 vehicles south of Ashdod and dropped his first bomb. In his second pass, he attacked from west to east and dropped his second bomb about one kilometer north of Ashdod. His third pass was from south to north. His cannons fired one round each and jammed. His machine guns worked fine. He landed at 2015.

Eddie Cohen was in radio contact with base. On his way back he reported that all was OK, that he saw the base and that he was about to land. From Ekron, he was not observed and he did not land there. Our men near Chatzor air base saw an aircraft engulfed in flames trying to crash-land two and a half kilometers distant. Two infantry platoons were sent immediately but the Egyptian forces were the first to reach the location. It is thought that Eddie Cohen mistook Chatzor for Ekron and tried to land there with his damaged airplane. (Cull et al 1994, Huertas 1998)

Alon's guns had also jammed. Upon landing, it was discovered that only half the fuel tanks in the S-199s had been filled. (For more on the first attack, read the account in the Chronology or in one of the participating pilots' bios.)

While the eight 70-kg bombs and limited strafing did not do much physical damage to the Egyptians, the revelation that Israel could field true figher aircraft gave them pause. This attack, and further bomb runs that night by the light aircraft of Tel Aviv Squadron and a C-46, froze the Egyptians in place. They advanced no further than that point and were eventually driven back in the October offensive. It can be fairly concluded that the existence of Israel as we know can be owed to this pathetic little attack.

The first S-199s to arrive in Israel arrived inside C-46s at Ekron, as part of Operation Balak, and were assembled there. 101 Squadron stayed at Ekron until a June 1 REAF Spitfire raid on that field damaged a pair of S-199s awaiting assembly in a hangar. The effectiveness of the raid, and the revelation that Egypt knew where Israel based its fighters, convinced the air force to pull the unit back from the front lines somewhat and move it north. Alon and Weizman chose the destination, Herzliya. It had a 2,000-m unpaved runway aligned north/south that was bulldozed amid orange groves. Weizman claims that one of the reasons they chose this field was because they felt the unpaved strip would handle the uppity Avias somewhat better than concrete, but Syd Cohen believes the softer surface actually promoted accidents. The move took place the first week of June.

By the end of May, 20 Balak flights had transported ten S-199s to Israel (and lost another in a crash), among other equipment. By mid June, three had been lost - those flown by Eddie Cohen (by convention D-101) and Rubenfeld (D-102), and another written off, probably the one flown by Alon on May 29 (D-103) or the one flown by Weizman the next day (D-104). D-105 was damaged and in repair and two uncompleted Avias had been damaged in REAF ground attacks on June 1. Five more arrived during the first truce, June 11 to July 9, and all but one of the rest arrived by the end of July. By the time fighting intensified on July 9, 101 Squadron had achieved a 1:1 pilot to plane ratio on paper, although the number of serviceable S-199s was almost always limited to four or fewer.

The unreliability of the S-199s was made painfully obvious as the war entered its secound round on July 9. The IDF ordered the Cheyl HaAvir to attack Egyptian airfields and positions the evening of July 8 in order to soften defences and secure air superiority for the coming battles. Four of 101 Squadron's S-199s were assigned to attack Al Arish air base, but the aircraft were only ready the next morning. Of the four, one was disabled in a take-off accident and another, with Bob Vickman aboard, was lost. The next day, another S-199 would be lost along with Lionel Bloch.

The S-199s hid one fatal flaw - literally. The cowl machine guns were not always synchronized with the propeller. Syd Cohen discovered the problem on July 11 on his first operational flight. Cohen decided to test-fire his guns and in doing so he may have saved his life and the life of anyone who would take up a S-199 in the future. When he fired his cowl guns, he holed his propeller but he was able to make it safely back to Herzliya.

The exact reason for this remains unclear. The synchronization gear may have been ill-suited to the Ju 211F's extra-wide propeller. Some of the pilots felt that perhaps the Czechoslovakian mechanics deliberately misfitted it. Maybe the gear itself malfunctioned with wear. Regardless, this was the first evidence of the phenomenon that the squadron could examine. The squadron pilots blamed the losses of Bob Vickman and Lionel Bloch in the two days previous squarely on this malfunction.

Red Finkel didn't trust the machine guns:

One time Rudy and I were out shooting a train. I'd used up all my 20-mm and stopped. I didn't want to take the chance of shooting my prop off and being captured. When we got back, Rudy called me on it. I had to find some reason to tell him, because I didn't want anybody to think I was yellow. I told him that I had to keep my machine gun ammo in case an enemy plane intercepted me on the way home. (Finkel, pers. comm.)

By July 29, Israel had eight or nine S-199s either in service and a few in repair. About half-a-dozen of the aircraft had already been written off. Numbers stayed steady as with the last arrivals entering service by Sept. 17, by which time several more had been struck off duty (D-109, 111, 112, 115, 122).

By the eve of the Operation Yoav, the mid-October offensive, only about a third of the 23 that were delivered up to that point (one lost in transport crash, one impounded in Greece) could answer the call (D-108, 113, 114, 117, 120, 121, 123, and maybe more). In the opening strike of that offensive, on Oct. 15, Modi Alon led a flight of three S-199s from Herzliya (four had been planned but one went unserviceable) over the Mediterranean, where they met up with two C-46 bombers and two C-47 bombers (using external electric bombracks for the first time; three were planned, but only two had been armed in time). The fighters took up station ahead of and below the bombers as the formation continued out to sea until the shore disappeared from sight. The planes turned south, then back east to approach the the target, Gaza, from out of the sun. Alon's charges, very late to target, meted out little physical damage.

At 07:00 on Oct 16, two S-199s performing defensive combat air patrol (CAP) intercepted two REAF Spitfires - by this point undoubtedly Mk IXs. After a brief fight, the Egyptians fled. One had suffered damage. The next pair up included Maury Mann, who suffered a mechanical failure and had to make an emergency landing at Kfar Sirkin. He hit hard, wrecking the airplane and suffering injuries in the process.

In general, the S-199s in Operation Yoav were meant for CAP while the Spitfires undertook most escort and attack missions. Air HQ adjusted this plan once they realized the REAF was not willing to challenge Israeli fighters, and started to task the Avias with close support ground attack. Two meant for CAP attacked Egyptian forces at Iraq al Manshiya instead.

On October 16, as a result of the air bombardment the day before and a successful Israeli army offensive during the night, the Egyptians began to retreat from Ashdod, where they had holed up since May 29, to Majdal. Air HQ ordered the 101 to harass the retreating armor.

In the afternoon, Modi Alon and Ezer Weizman took two S-199s - Alon in D-114 and Weizman in D-121, both with two 70-kg bombs - to attack the fleeing Egyptians. Weizman recalled:

We took off, flying low and maintaining radio contact. We flew along the coast and I dropped my two bombs on the center of an Egyptian concentration. I continued on to Majdal, strafing with my machine guns. We lost contact with one another and each of us returned separately. Before landing back at Herzliya, I noticed a pillar of black smoke near the airfield. (Cull et al 1994)

Alon had arrived first. His gear wouldn't descend so he tried to shake it down. Syd Antin, manning the control tower, spotted an unidentified aircraft at treetop level to the west and radioed the news to Alon, who interrupted his maneuvering to check it out. Once he had identified the bogey as a friendly, Alon resumed the high-G maneuvers.

Alon had managed to get one wheel down when Antin noticed a wisp of smoke coming from Alon's S-199. He asked Alon to check the engine temperature, and Alon radioed that it seemed fine. Alon's second wheel came down and he made his final approach, but Antin thought the plane was too slow and descending too fast. Antin shouted at Alon to "Get it up! Get it up!" (Yonay 1993) but the plane crashed short of the runway and exploded. The official report read:

Aircraft returned from mission and pilot could not lower landing gear. After circling for some time, one leg came down. Pilot continued circling, trying to lower other leg, when engine cut out. Aircraft crashed out of control, burst into flames and was completely destroyed. (Cull et al 1994)

Alon crashed at 17:45. Eyewitnesses reported that D-114 had entered a power spin at 1,000 feet. Antin thinks Alon pushed his engine too hard in the chase after the bogey and overheated his engine, leading to that wisp of smoke and glycol fumes in the cockpit. He thinks Alon eventually passed out in the fumes as indicated by his unresponsiveness and the way the S-199 so effortlessly augered in.

By the middle of December, 101 Squadron was down to six S-199s (D-108, 118, 120, 121, 123, and 124) and would lose one of those to a take-off accident on Dec. 15. Considering the low service rate of the type, the S-199 performed in its limited role far beyond any reasonable expectation. Combat damage, accidents, and malfunctions meant that after May 29, the very first day of S-199 action, no more than three of the 25 purchased Avias were ever airborne at the same time. The squadron came close on July 9, but one of the four S-199s meant to fly that day suffered a take-off mishap and never got up.

The Israeli delegation in Czechoslovakia complained in August about the reliability and poor performance of the aircraft to the Czechoslovakians, but the latter blamed rusty pilots unfamiliar with the type. There may be a grain of truth in that, but there's no question 101 Squadron succeeded to some degree despite and not because of their airplanes.

![]()

The

following list identifies the S-199s that saw action in Israel during the War

of Independence.

The

following list identifies the S-199s that saw action in Israel during the War

of Independence.

Besides a standard lack of knowledge, there is a lot of confusion in two areas. Some sources believe that the initial delivery of S-199s were naturally numbered D-101 to D-104 but newly discovered photos show no serials on these aircraft. D-105 was most likely the first to wear a serial number.

| D- # | 19XX | Arrival as freight | Last flight | Last Pilot | Notes |

| D-101 | * | May 20 | May 29 | E. Cohen | Lost on initial mission |

| D-102 | * | May 21 | May 30 | Rubenfeld | |

| D-103 | * | May 22 | May 29? | Alon? | In CMU in July |

| * | May 23 | n/a | Balak 11 | Written off after crash | |

| D-104 | * | May 25 | ? | ? | Weizman bird strike |

| D-105 | * | May 25 | June 10 | Alon | Twice hit by AA |

| D-106 | * | May 30 | June 11? | Lichtman? | Alon's two kills, June 3 |

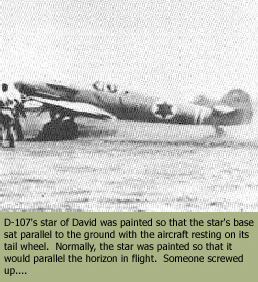

| D-107 | * | May 30 | Aug. 2 | Jacobs | Failed test flight |

| D-108 | 1906* | May 31 | Dec. 26 | survived war | |

| D-109 | * | May 31 | July 6 | Andrews | Flips on takeoff |

| D-110 | * | July 1 | July 9 | Vickman | Lost over Gaza |

| D-111 | July 1 | July 18 | Antin | Landing accident | |

| D-112 | July 4 | July 10 | Bloch | Lost near Quneitra | |

| D-113 | * | July 7 | Oct. 16 | Frankel | Loss of oil pressure; bellied in. |

| D-114 | * | July 9 | Oct. 16 | Alon | Alon KIA |

| D-115 | * | July 13 | Sept. 8 | Jacobs | Landing accident |

| D-116 | * | July 14 | July 29 | Horowitz | Overheats; landing accident |

| D-117 | 1901 | July 15 | Oct. 17 | Lichtman | hit by AA, bellies in at Aqir |

| D-118 | 1902 | July 17 | Dec. 14 | survived war | |

| D-119 | July 18 | Oct. 8 | Pomerantz | photo recon; landing accident | |

| D-120 | 1903 | July 19 | Dec. 22 | survived war | |

| D-121 | 1904 | July 20 | Dec. 22 | survived war; in IAF Museum | |

| D-122 | July 24 | Sept. 16 | Horowitz | Takeoff accident | |

| D-123 | 1905 | July 28 | Dec. 24 | survived war | |

| D-124 | 1907 | Nov. 26 | Dec. 15 | Peake | Flips on takeoff |

* = had oil-cooler scoop

Aircraft histories that need an update to be accurate:

D-101 and D-102

Both these aircraft flew on the initial May 29 ground attack near Ashdod. One was (probably) shot out from under Eddie Cohen on that mission. The other suffered damage the next day while Rubenfeld used it to attack Arab forces near Tul Karm. He had to bail out and the plane was lost.

D-103 and D-104

Both these aircraft took part in the May 29 Ashdod attack. Both were in the Central Maintenance Unit in July.

D-105

Damaged in Modi Alon's June 6 ground attack and still with the Central Maintenance Unit in late July.

D-106

No information.

D-107

Re-entered service on July 10 but only for a day. Lionel Bloch took off to attack Syrian Harvards and succumbed either to their guns or shot off his own propeller in his attack. He crashed near Quneitra.

D-108

D-108

Flown in formation by Mitchell Flint on Aug. 17.

Mitchell Flint crashes D-108 on landing on Aug. 21. It re-enters service after repairs.

D-109

With the Central Maintenance Unit in late July before being written off.

D-110

One story holds that Eddie Cohen flew D-110 on its one and only mission on May 29 to bomb Egyptian forces at Ashdod. On fire - probably hit by AA - the plane crashes short of Chatzor, killing Cohen. There's no question that Cohen died in this manner (see his biography entry), but the no one knows for certain which Avia he was in.

The Jan. 2, 1949 edition of the Egyptian newspaper "Al-Aharam" contained a photograph of the remains of D-110 (left). This is almost certainly one of three aircraft, the only three S-199s to be lost over Arab territory: the airplanes flown by Eddie Cohen, Bob Vickman, or Lionel Bloch.

Cohen

was shot down over Egyptian territory May 29. On 9 July, Vickman flew into the

sea off Gaza and Bloch crashed near Quneitra after engaging Syrian Harvards

over Mishmar HaYarden.

Cohen

was shot down over Egyptian territory May 29. On 9 July, Vickman flew into the

sea off Gaza and Bloch crashed near Quneitra after engaging Syrian Harvards

over Mishmar HaYarden.

We know that the early S-199s had an identifying feature: the dalet (D) and the number portion of the D-1XX serial were on opposite sides of the roundel (see the photo above the table). But D-110 has them together. This seems to indicate that D-110 was not one of the originals and that Cohen was not flying this one, although Cull et al (1994) claim he was.

Cull et al also say that Bloch was probably flying D-107 and most sources agree. However, that would mean that Vickman had been flying D-110. That in turn would mean either that the Egyptians had fished his S-199, or parts thereof, out of the sea near Gaza or that Vickman had in fact crashed on land.

The current evidence, taken at face value, seems to be that Egyptian divers fished out part of Vickman's S-199 from the water. I have no evidence to suggest otherwise, but my hunch is that in fact Bloch flew D-110 and Vickman flew D-107. Proving that will have to wait until I can get my hands on some archived records.

D-111 and 112

With Central Maintenance Unit in late July and probably written off.

D-113

Ground-looped by Leo Nomis on Aug. 9, but undamaged. Landed in a minefield by Leon Frankel on Oct. 16 and written off.

D-114

Modi Alon flew this plane the flight he was killed.

D-115

Sandy Jacobs had a landing accident Sept. 9 and the aircraft was written off.

D-116

With Central Maintenance Unit in late July, presumably being assembled for the first time. This may be the aircraft that Cyril Horowitz damaged in a landing at Herzliya in August. It was back in the Central Maintenance Unit in November.

D-117

Mitchell Flint makes a wheels-up landing on Aug. 20. It re-enters service after repairs only to have Giddy Lichtman belly it in at Ekron Oct. 17 after suffering damage to the "cylinder exhaust stack, right wing, and in right radiator, while loss of coolant caused internal damage to engine" in an attack on Iraq al Suweidan.

D-118

Giddy Lichtman flew this S-199 on Sept. 22 and shot down an Arab Airways Dragon Rapide. The airplane survived the war and was transferred to Ekron, renamed Tel Nof, in 1950.

D-119

This was a unique S-199 as it was coverted for photo-recon duties. Mitchell Flint flew it on Aug. 19. Bill Pomerantz ended its service career with a landing accident, Oct. 8.

D-120

Cull et al (1994) imply that from May 31 to June 4, when Baron Wiseberg totaled it, the S-199 designated D-120 was Israel's only serviceable combat aircraft. Modi Alon and Lou Lenart alternated twilight patrols over Tel Aviv. On June 3, Alon's turn in the cockpit, it shot down two REAF C-47 bombers. Earlier in the day, Alon had damaged an REAF Spitfire.

It is unlikely that D-120 had been delivered so early, however. Bill Pomerantz ground-looped it Sept. 14, but the aircraft was repaired and soon ready for duty again. It was transferred to Tel Nof in 1950.

D-121

Leo Nomis had a landing accident Sept. 5. Rudy Augarten shot down a REAF Spitfire with this airplane on Oct. 16. Weizman also flew this plane that same day, accompanying Alon on his fatal sortie. D-121 survived to be transferred to Tel Nof in 1950.

D-122

Mitchell Flint has two sorties on August 15. Written off after Cyril Horowitz's take-off accident, Sept. 16.

D-123

D-124

Held in Rome onboard a C-46 (RX-134) from July 18 to November. Once in service, it had a short career, being written off after Wayne Peake flipped it on take-off, Dec. 15.