George Lichter

George Lichter George Lichter

George Lichter

Brooklyn, New York

Combat Record

WWII: 2 kills (one Me 109, one FW 190), 3 probables, 1 damaged

Story

George Lichter flew P-47C/Ds and P-51Ds in Europe with the USAAF's 374th Fighter Squadron (361 FG) From November 1943 to just before the Battle of the Bulge, December 1944. After the war, he jumped between jobs, at times selling used clothing and general merchandise in China. In November 1946, on his way home across the Pacific by boat, Lichter stopped in Hawaii and got a job flying a Dakota to the mainland for Kirk Kerkorian (now owner of MGM, among other pies).

Lichter started up a textile business in New York with two brothers. One of his clients impressed him with her opinions of American Jews and their donations to Israel, that they never give enough, only what they have in excess.

When Israel declared statehood, Lichter decided to volunteer his services. He didn't know how, and called three or four organizations, all of whom told him they knew nothing about it, either. One of his calls must have reached someone who knew something, however, as he soon received a phone call requesting that he attend a clandestine meeting at a hotel.

Lichter felt pessimistic about Israel's future, but he wanted to "give enough". He thought that the Arabs would overrun and dismantle the country within a month or two. He "had no concept that there was a possibilty of Israel winning the war."

After

renewing his passport and acquiring a $480 one-way ticket to Geneva, Lichter

left. A contact in Switzerland sent him by train to Zurich and from there on

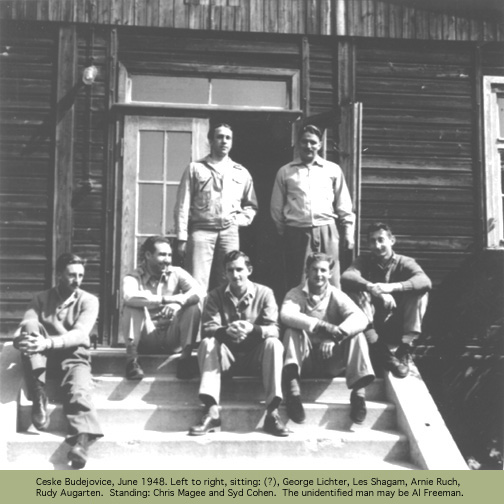

a plane to Prague, where he met a group of other volunteers including Chris

Magee, Arnie Ruch, and Les Shagam. The group traveled together to Ceske Budejovice,

arriving in early June.

After

renewing his passport and acquiring a $480 one-way ticket to Geneva, Lichter

left. A contact in Switzerland sent him by train to Zurich and from there on

a plane to Prague, where he met a group of other volunteers including Chris

Magee, Arnie Ruch, and Les Shagam. The group traveled together to Ceske Budejovice,

arriving in early June.

Lichter, like many of the pilots, had not flown in a while and first checked out in Arado trainers. After that, the Czechoslovakian instructors - lieutenants Bilek and Prokopec - introduced him and the others to the S-199. After about a week, several pilots had checked out and were on their way to Israel. Lichter, however, was asked to stay behind.

After leaving combat flying in Europe, Lichter had done a stint training students, training a class of Brazilians and another class of Americans bound for Japan (in the P-47N). After the war, he had earned his civilian training rating, too.

The combination of Lichter's trainer qualifications, his adeptness in handling the stubborn S-199s, and the fact that the Czechoslovakian trainers didn't want to fly the planes anymore led the Czechs to ask him to take over the training program. Lichter stayed at Ceske Budejovice airfield through the summer, sleeping on "terrible army cots in a bare room" and eating "monstrous" food.

As a trainer, Lichter introduced a philosophy completely alien to the Israelis he taught. The native Israeli cadets he later taught - including Haifa dandy Dani Shapira, kibbutznik Moti Fein (later Moti Hod), and Shaya Gazit - had experienced only informal military organization with the Haganah or Palmach, if any at all. Lichter took a stricter, more disciplined, more American approach to training. He demanded that his cadets follow his rules and he was quick to reprimand slackers. Several of his students confessed to fearing the man as much as they respected him.

As the summer wore on and classes passed under his tutelage, Lichter took on more and more of the training responsibility - both because he was so talented in the S-199 and because the less the Czechoslovakian trainers flew the S-199, the happier they were. He would fly the S-199 a dozen times a day when the going got busy. Red Finkel said:

George was the one true hero of the 1948 war. Those planes were so dangerous, I remember seeing him at the end of a day of instruction, and he'd be so shook up he'd head straight for the bar, and couldn't even talk until he had a drink. (Yonay 1993)

In early July, Leo Nomis and Mitchell Flint fell into Lichter's hands. Nomis rcalls his first meeting with Lichter:

The driver points to the stocky one and says this is George Lichter.... Lichter leans back in his chair and studies me for a moment. He has a short black beard and his eyes are serious. (Nomis and Cull 1994)

Once comfortable with the S-199 - at least, as comfortable as possible - Nomis engaged Lichter in mock dogfights.

A few yards to the right Lichter starts his engine and the noise is loud. I switch the radio on and the sound dims amid the crackling of the static in the helmet earphones. I work the fuel primer pump and the Messerschmitt rocks gently as the mechanics wind the inertia. The engine starts and the rhythmic rumbling creates a relaxing effect. I look over at Lichter and he moves forward from the line with rudder fishtailing. I turn out behind himand we take off into the bright air.

Lichter handles his machine deftly. We have a simulated dogfight at 10,000 feet and I watch as the patchwork of the earth below tilts diagonally. Then the wings of the aircraft in front flash upward and the windscreen is filled with the blue above. Lichter rolls while climbing, tightens the roll into a turn and drops out behind me. I smile to myself. It is two years since I have flown fighters. (Nomis and Cull 1998)

By the end of the summer, all the S-199s had left for Israel. Mitchell Flint arrived in Israel in early August and Lichter either came with him or followed soon after. He sought and been granted combat duty in Israel. Assigned to the 101, Lichter was in Netanya in mid-August, around the time of Ben-Gurion's visit. Nomis remembers:

Lichter is going back to a European assignment in a week and he stays temporarily in the tent with us. There are no more Messerschmitts coming in from Czechoslovakia but Lichter says they are trying to make a deal for Spitfires. We all smile but Lichter looks unelated. He says the Czechs want a hell of a lot of money for them. Before he leaves Israel, Lichter puts on an admirable display of aerobatics in the clear morning air at Netanya. (Nomis and Cull 1998)

Soon, despite promises to allow him to fly combat after the second truce, Lichter again found himself on the way back to Czechoslovakia. Having bought Spitfires from that country, Israel needed someone to teach Israeli cadets how to fly them. He, along with Jack Cohen, also served as test pilot for the Spitfires Sam Pomerance modified for the Velvetta flights - all the armour and radios were removed to allow the aircraft to carry more fuel.

In December, Lichter played a leading role in Velvetta 2. After a delay caused by winter storms, on Dec. 18, six Spitfires left Kunovice, Czechoslovakia. Sam Pomerance led Caesar Dangott and Bill Pomerantz while George Lichter led John McElroy and Moti Fein, still a cadet but chosen because of his aptitude. In the low visibility conditions, Bill Pomerantz quickly lost the others. With the cloud cover still solid at 14,000 feet, Lichter decided to lead the rest back to Kunovice. Pomerance, who with Lichter had the only airborne radios, told Lichter he'd press ahead.

Pomerance died when he crashed into a mountain in Yugoslavia. Pomerantz ditched in Yugoslavia and although his aircraft was written off, he suffered only minor injuries.

The next day, the Velvetta 2 pilots made a second attempt. John McElroy, a veteran of Spitfire ferry operations to Malta, was angry over the failure of the day before and refused to follow a less experienced pilot a second time.

Lichter led six Spits in another attempt to reach Niksic. Lichter (in Spitfire 2010) led Moti Fein and Dani Shapira, another promising Israeli air cadet in training in Czechoslovakia. John McElroy led Caesar Dangott and Arnold Ruch. The clouds still blanketed the terrain.

Lichter decided to fly over Hungary to the Adriatic Sea. After several hours of dead reckoning, he led the flight down into the cloud cover. Shapira suffered disorientation:

The experience of Moti and myself in close formation flying was limited to several flights in the Arado. McElroy was so close to Lichter that, when he closed the formation in the clouds, I could see his propeller underneath the tail of Lichter's Spitfire.

George had the maps and he navigated. My only chance to survive was to stick close to my leader. At one stage, in the clouds, I lost contact with George. I panicked so I turned to starboard to avoid a collision and it was the first time in the flight that I looked at the instruments: I saw that I was losing height, with speed increasing and I did not understand what was happening. (Cull et al 1994)

Shapira was about to bail out when Lichter found him.

I had opened the canopy and then saw two Spitfires passing very close, with the other three behind them. George was waving his hands. He saved my life. When we reached the coast of Yugoslavia the weather improved, but for some three hours we had flown in bad weather. We continued along the Adriatic coastline and then turned inland and all six Spitfires landed simultaneously.... (Cull et al 1994)

At 300 feet, they broke out of the clouds above the waters of the Adriatic and followed the coast. Despite a minor fuel leak in Fein's plane, all made it safely.

On Dec. 23, Lichter, Dangott, Fein, and Shapira left Niksic for Israel in Spitfires painted in Israeli colours. Lichter spent the rest of the war in Israel.

In early February 1949, Lichter went to Prague and married a woman he had met in Czechoslovakia. He and his bride returned to the US where he sold his textile business. The two of them returned to Israel in the summer. The Air Force assigned Lichter to 101 Squadron, now at Ramat David under the command of Ezer Weizman, but he languished, essentially ignored. Fed up, he complained to IAF HQ, which transferred him to Ekron to become the chief test pilot there. His next assignment was to head the IAF's advanced flying school.

Lichter and his wife left Israel in January 1951.