Please bear with me as I interrupt my car rants to answer a question about - gasp! - storytelling.

Naila asked, "How do you get started, writing, when you have an idea?"

I'm going to limit my answer to writing stories for the screen, since that's what I've been doing lately.

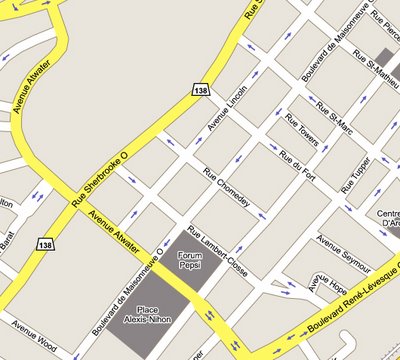

My first encounter with people who wanted to write screenplays was an eight-week screenwriting course offered through the

Quebec Writers Federation, with playwright/screenwriter David Sherman as the instructor. There were 13 of us in the course, and the broadest stroke I learned there was what makes a story.

Many of the students did not know how to construct a story. What they came to class with were settings.

And that is my step one - fundamental, but no less explicit for it. Make sure you have a story, and not just a setting. What happens? Once you decide what happens, you can decide where it happens.

There are a couple of ways to look at what happens, however. There's plot and there's theme. I don't have a hard and fast rule on which comes first. Of the last three features I've written, "101" and "Sheep's End" started with plot, "By the Book" started with theme. Once I had the plot of "Sheep's End" down, more or less, in my head, I began the hang a theme on it. "101" grew a theme as I wrote it, and it suffers as a result. I won't rely on that method again.

Once the story is roughed out in my head, I rough it out on paper. Read five technical screenwriting books and you'll get five ways to structure a story. Any structure will work, as long as it has a beginning, middle, and end. That's universal. That's what makes a story a story.

I always seem to think of the end first. Many writers invent the characters and let them take the story where it goes. Not me. I need a goal. I invent the ending first, then the beginning, and then the infamous second-act journey, the middle.

With the idea bubbling in my head, pen hits paper - literally, since I work in longhand initially. Again, I took three different approaches on my last three scripts.

With "101", I tried to follow

Syd Field's three-act structure. First, I wrote out scenes on index cards. That gave me a way to gauge the story as it grew. I could shift and change scenes as needed. That worked well enough.

For "Sheep's End", I followed the structural advice found in Christopher Vogler's "

The Writer's Journey". I had some fun with that as I played with his theories - for example, having my heroes enter a cave when Vogler discusses metaphorical caves. I also used index cards for this.

I did not use index cards for "By the Book". I outlined scenes on a notepad. I think I prefer that method. The index cards seem disjointed. I don't think it matters either way. In terms of structure, the eight-sequence structure

as digested by Warren Leonard. I departed from that structure freely when I needed to, but his method helps break down an outline into manageable chunks.

Once I have an outline done, I start writing, eventually. I'm a great editor, but I'm horrible at editing myself. I need to forget about something before I come back to it, so I try to set aside an outline for weeks or months before I come back to it. That doesn't always work, because my stories incubate even when I don't look at them. I'm constantly jotting notes down for all of them - but even that is helpful. The earlier in the process you can improve the story, the easier it is to do.

By this time, I've typed the outline into a text document on my Mac. I type the scenes directly on the computer.

"By the Book" is the only screenplay for which I've written a treatment. A treatment is not easily defined. I've seen treatments five pages long, but James Cameron's treatment for "Titanic" is said to have run 75 pages. For my treatment, I followed Alex Epstein's example. One of the benefits of working for him is what I get to read.

I can best describe my treatment as a screenplay without the dialogue. I write down the actions, the motivations, the reactions. I wasn't sure how long it would be, but I got to 30 pages using screenplay format. I'm confident that once I detail it and add dialogue, it'll reach 100 pages. At least, that's what I'm expecting.

Here's a small sample of the treatment, so you can see what I mean (Daniel=father; Emma=mother; Mel=boarder; Peter=a fraternal twin, one of three kids):

- Daniel leads a family meeting. It’s an interrogation of the children, with Emma but not Mel in attendance.

- Daniel carefully asks the children who used his tools. Too quickly, Peter says, "Not me." The boy's obviously lying. Daniel gives Peter three chances to tell the truth. The boy won't own up.

- Daniel sends Peter to his room.

- Peter wails. Emma wants to go to him, but Daniel forbids it.

- Out of sight of Daniel and Emma, Mel sneaks out of her room to go to comfort the boy.

- Daniel pauses to gather strength. He lays out his plan for the day, which concludes with a pick-up basketball game that night.

- Emma forgot to tell him about plans she'd made in his absence for a potluck dinner with some friends from church. Emma had promised the dinner a pot of Daniel's chili.

- Daniel takes this in stride.

- Emma says she was about to go out and get him the ingredients, but they can cancel if he prefers. Daniel agrees to her plan: it’s not too much of a hardship to cook and do work on the house at the same time, so long as the kids stay out of trouble in the kitchen.

That will obviously expand as I add dialogue and more detail.

Bonus comment on "Sheep's End":

The "Sheep's End" screenplay received a pleasantly positive critique from a reviewer steeped in literary criticism. She used the word "leitmotif" and compares "Sheep's End" to the work of German dramatist

Heinrich von Kleist. Pretty good for a piece that uses the word "ass" 17 times, don't you think?